Yansu Qi , Han Li , Xiuhe Yuan , Dongmiao Zhao and Chao Liu

Applying Machine Learning to Explore the Impact Mechanisms of the Urban Built Environment’s Characteristics on the Thermal Environment

Abstract: Recent studies on the thermal environment in cities have concentrated on the macro-scale level, with limited attention given to specific built-up areas. Additionally, there is scarce research on the comprehensive effects of the physical features of urban spaces on their thermal environment, especially on the regional scale. We explored how urban built environment factors influence the thermal environment using Qingdao as a case study. A neural network model with a feed-forward architecture was employed to map the complex interactions between land surface temperatures and built environment characteristics. The model’s performance was compared with traditional methods. Various built environment factors were analyzed, considering both spatial and morphological features, with data sourced from multiple channels and pre-processed for quality. The Shapley Additive exPlanations method was applied to interpret the impact mechanism, quantifying the contribution of each factor. The results indicate that an impervious area percentage significantly increased the land surface temperature in the summer, while vegetation coverage and building density helped maintain surface temperatures during the winter. This study presents quantitative insights into the importance, direction, and critical impacts of variable urban factors on the thermal environment. The findings provide useful directions for urban design and rehabilitation, especially in reducing the environmental impacts of urban heat islands.

Keywords: Deep Learning , Remote Sensing , Shapley Additive exPlanations , Urban Thermal Environment

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization has introduced several challenges to the urban environment, with one of the most significant being the degradation of the thermal environment. This urban expansion, marked by increases in buildings and impervious surfaces, has resulted in a decline in natural vegetation and aquatic ecosystems [1]. Urban surfaces absorb and retain heat, culminating in elevated urban surface temperatures. Additionally, urbanization has significantly contributed to thermal pollution. The activities of transportation, industry, and energy consumption within urban areas release substantial quantities of heat and waste heat [2], resulting in the accumulation of thermal pollution within the urban atmosphere. This phenomenon contributes to the deterioration of air quality in cities, rendering living environments discomforting and adversely impacting human health [3]. Furthermore, the interplay between urbanization and the thermal environment can give rise to additional challenges, including reduced precipitation and wind speeds and poor dispersion of atmospheric pollutants [4].

Given the significant challenges humanity faces, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms through which urban development and construction impact land surface temperatures (LSTs), particularly on the mesoscale. Remote sensing and geographic information system (GIS) tools offer valuable data and technological tools that enhance our understanding of the urban thermal environment. With the advent of big data, the Internet of Things (IoT) and machine learning have become essential tools in urban planning and development. Feed-forward neural network (FNN) is now extensively employed in various applications within this domain [5]. While deep learning models can automatically learn complex feature representations and patterns from large amounts of training data, their decision-making process becomes opaque. Previous research has focused on city-wide analyses overall; there is limited understanding of the specific built-up areas and their individual contributions to the thermal environment.

We explored how urban built environment characteristics influence the thermal environment. To achieve this, we employed a FNN to accurately capture these complex relationships. We compared the FNN model with multiple linear regression (MLR) and random forest (RF) to assess its accuracy. Moreover, we applied the Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method to explain the LST prediction model and analyze the underlying impact mechanism. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

· We employed a high-precision FNN to model the nonlinear relationships between urban built environment characteristics and LST.

· We used the SHAP model to quantitatively analyze the importance, direction, and threshold phenomena of various factors, providing clear insights into how different urban characteristics influence temperature variations.

· We offer practical recommendations for urban designers by revealing the specific ways that built environment characteristics affect the thermal environment.

2. Related Works

Research on the urban thermal environment encompasses various factors, such as urban development, climate change, and human activities. Current studies focus on understanding the dynamic characteristics, formation mechanisms, drivers, and corresponding planning strategies of the urban thermal environment. In this context, the built-up area plays an important role in developing the urban thermal environment, representing the existing physical space within the city. Evaluating the built environment requires the use of diverse indicators and dimensions to progress urban planning and construction toward greater efficiency, diversity, and sustainability. Handy et al. [6] proposed six built environment characteristics, including density, land use mix, regional structure, esthetics, neighborhood scale, and street connectivity. Guerri et al. [7] examined the correlation between urban heat islands and urban morphological features, considering 10 urban space indicators, including the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), water index, impervious areas, and average population density. Chiang et al. [8] explored the influence of architectural environmental features on pedestrian comfort using indicators such as the sky view factor and greenery index. By employing these indicators and considering various dimensions, researchers aim to evaluate the built environment and facilitate urban planning and construction that align with efficiency, diversity, and sustainability goals.

The built environment encompasses numerous dimensions and indicators, and its relationship with the thermal environment is highly intricate. Previous studies utilized multivariate linear regression models, RFs, and other methods [9,10]. Nevertheless, big data and deep learning technologies provide better opportunities to explore and learn more about urban thermal environments. Through the application of these advanced technologies, we can strive for smarter, more efficient, and sustainable urban thermal environment management and planning. The FNN is widely used owing to its powerful modeling capabilities; it is regarded as one of the core models in machine learning. The FNN is widely applied in diverse fields, including energy, buildings, cities, and economy due to its versatility and effectiveness [11]. Its design and training typically involve the backpropagation algorithm, which continuously updates network parameters by minimizing the error between predicted and actual outputs, thereby improving the model's accuracy. Dai et al. [12] successfully achieved the multi-objective optimization of train head shape by utilizing the FNN model, offering valuable guidance for enhancing the performance of high-speed trains. Additionally, de-Miguel-Rodriguez et al. [13] employed the FNN model to calculate the capacity of low-rise reinforced concrete buildings, achieving the swift and precise assessment of seismic vulnerability in built-up areas. A dual-layer FNN is used to capture the relationship between static background characteristics and homographic features in unstructured motion videos. This enabled them to compute the image coordinates of chosen features in their stationary positions and to account for camera movement. These examples illustrate the versatility and effectiveness of the FNN, highlighting its capability to be trained and learn from real data in diverse fields of application.

The FNN model can be considered a black-box model, while deep learning models inherently exhibit black-box characteristics. Various techniques can help mitigate this issue, including using interpretable deep learning methods, fairness-enhanced approaches, and adversarial sample defense techniques. SHAP values are a commonly used method to explain models in machine learning, helping researchers to understand the prediction logic of models and improve their interpretability [14]. The SHAP model was originally introduced to describe the process of how decisions are made in machine learning models, especially black-box models [15]. They can be used to explain models’ prediction results, including positive and negative contributions. Today, SHAP is extensively applied across disciplines such as social sciences and economics to analyze and quantify the influence of specific explanatory variables. Park et al. [16] used SHAP values to explain the comparative significance of 18 variables of inputs to chlorophyll-a, which provided insights to reduce the water quality analysis cost. Nishikawa et al. [17] used SHAP values to analyze a RF model developed to estimate the dry matter and nitrogen levels of pasture grasses, providing opportunities for detailed data analysis.

3. Methods

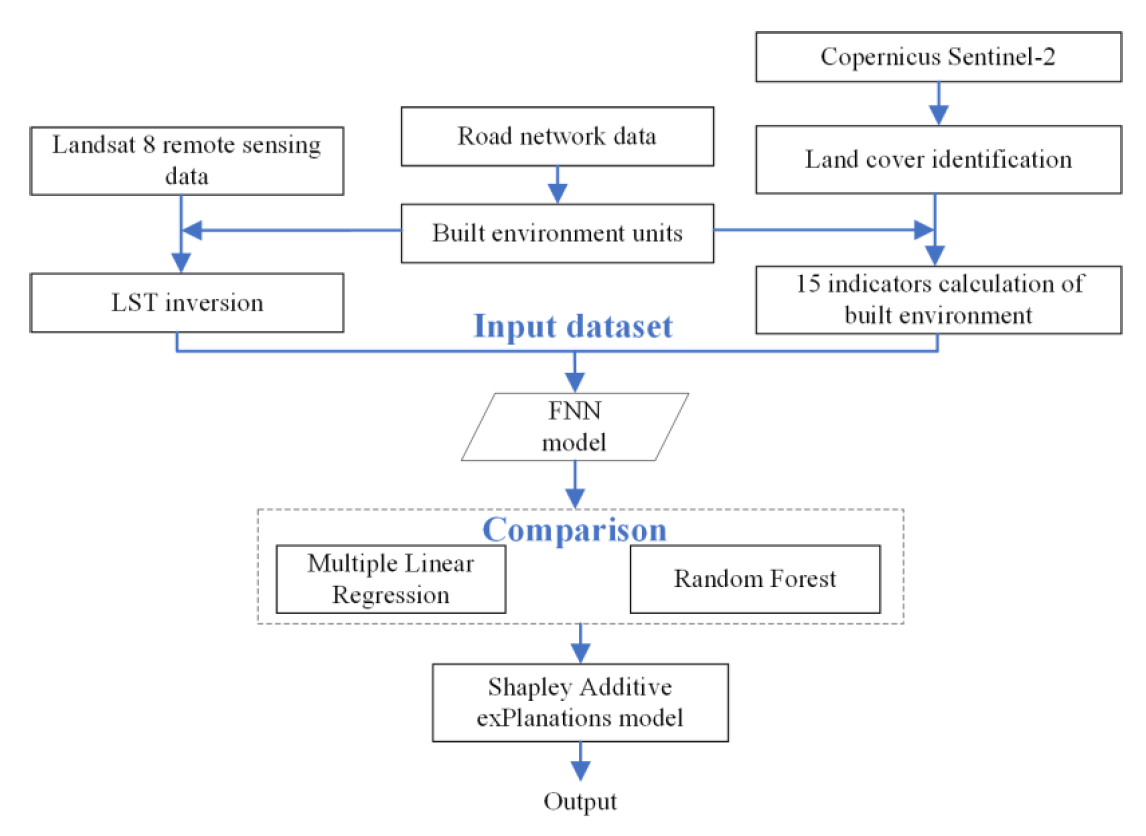

Utilizing diverse data sources, we analyzed 15 variables that impact the built environment’s role in shaping surface temperatures in coastal areas. The FNN model was constructed to represent the nonlinear impacts of the urban built environment on the thermal environment. To overcome the opacity of the neural network model, the SHAP method was introduced for model interpretation. By assessing the significance of the model’s features, this approach provides a deeper understanding of how different factors of the built environment affect the thermal environment, with the detailed process illustrated in Fig. 1.

3.1 Study Area

We selected Qingdao as a case study, and land use data were utilized to identify artificial land cover types. Qingdao, situated along the eastern coastline of China, possesses distinctive geographical and climatic characteristics. Its summers are characterized by warmth and a high humidity, while its winters are generally cold and dry. Due to the moderating effect of the ocean, it has a higher humidity and a more maritime-like climate compared to inland cities. The urban area of Qingdao has a relatively flat terrain without significant mountain barriers, making it susceptible to the influence of cold air from the land, hence the relatively cold winters.

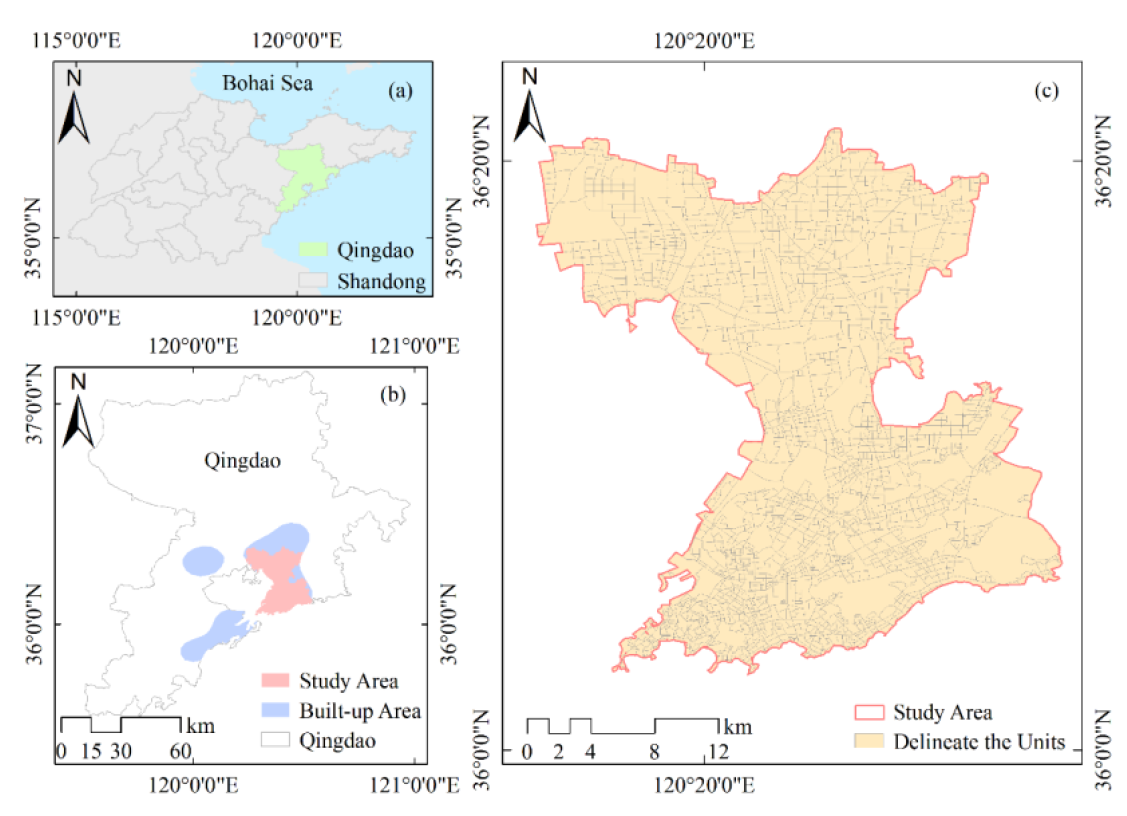

Fig. 2.

We applied the density analysis function in a GIS, incorporating parameters such as kernel type, kernel radius (bandwidth), and output resolution to extract built-up areas. As shown in Fig. 2(b), a threshold analysis was performed to recognize the built-up area with a range of 0.447–2.011. We focused on a region in Qingdao's old city, selected for its well-developed infrastructure, extensive transportation networks, and dense urban fabric. This area spans a total of 467,101,513.18 m2. In the complex system that is the city, the spatial features and the surface thermal environment have a complex and interrelated relationship. The results of scoping conducted by the city planning department based on existing roads were the fundamental dimensions of the urban spatial grid at the block level. To facilitate more detailed analysis, as shown in Fig. 2(c), there are 1,817 block units in the built-up area.

3.2 Multi-source Data Collection and Pre-processing

This study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the urban thermal environment in the study area. The motivation behind this choice stems from the need to integrate diverse data sources to capture the intricate relationships between built environment characteristics and surface temperature. The choice of dataset was guided by several key considerations, including data availability, spatial and temporal resolution, and relevance to the research objectives. Landsat 8 remote sensing data offer a moderate spatial resolution (30 m/pixel) and temporal coverage spanning multiple seasons, allowing for a detailed analysis of seasonal variations in the urban thermal environment. In addition to Landsat 8 remote sensing data, other datasets were utilized, including building data from Baidu Maps, road network data, and point-of-interest (POI) data. These datasets complement the remote sensing data by providing additional information on the built environment, such as the locations and attributes of buildings, roads, and facilities. Detailed information on the specific data and preprocessing tools is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Data type | Data source | Purpose | Preprocessing tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remote sensing data | |||

| Landsat 8 | https://www.gscloud.cn/ | Land surface temperature inversion | ENVI performs atmospheric |

| Copernicus Sentinel-2 | https://www.gscloud.cn/ | Identification of vegetation, water, and bare soil | corrections, radiometric corrections, clipping, etc. |

| DEM (12.5m) | https://www.nasa.gov | Calculate elevation | ArcGIS clip, etc. |

| Vector data | https://map.baidu.com | ArcGIS clip, etc. | |

| Building data | Building outline recognition | ||

| Road network data | Road network identification | ||

| POI data | Point-of-interest recognition |

The urban thermal environment data used in this study comprised Landsat 8 satellite remote sensing data acquired in August 2021 and December 2021. Based on the thermal infrared radiative transfer equation, infrared band data can be converted to effective bright temperatures and then to degrees Celsius from the sensor's spectral emissivity. The specific formula is shown in Eq. (1):

where [TeX:] $$T_s$$ represents the true LST, while “a” and “b” are constants with values of -67.355351 and 0.458606, respectively. [TeX:] $$C=\varepsilon \times t \text { and } D=(1-t) \times(1+(1-\varepsilon) \times t)$$ are also defined. [TeX:] $$T_a$$ represents the average atmospheric effective temperature (in units of K), and [TeX:] $$T_6$$ is obtained using Planck's equation.

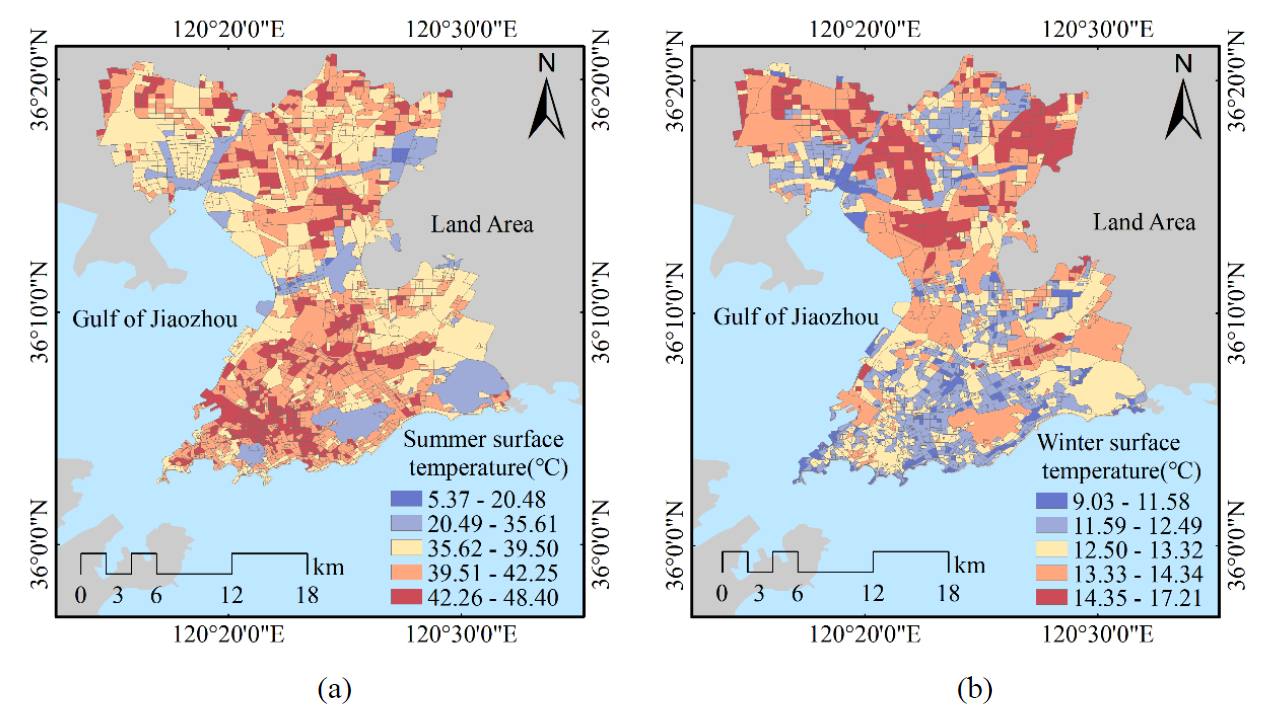

The spatial distribution map of LST in Fig. 3 reveals significant variations in urban areas. Specifically, Fig. 3(a) shows that the highest LST in the built-up area during the summer reaches [TeX:] $$48.4^{\circ} \mathrm{C},$$ while the lowest is [TeX:] $$5.37^{\circ} \mathrm{C},$$ with an average of [TeX:] $$40.35^{\circ} \mathrm{C}.$$ Notably, 54.10% of the units, or 983 units, have temperatures exceeding the average.

3.3 Built-up Environment Index

As a complex system, the urban thermal environment is affected by many factors, and this study considers the impact on the urban thermal environment from the perspective of the built environment. The three principles considered when determining impact indicators are (i) the objective characterization of the built environment’s spatial features; (ii) the potential impact on the urban thermal environment; (iii) and the ability to be artificially regulated. Land use encompasses factors that affect the absorption and retention of heat, such as the proportion of impervious surfaces, vegetation, bare soil, and water bodies. Building space relates to the physical attributes of built structures, including building density, floor area ratio, average building height, and sky view factor. Transportation layout considers the impact of road networks on the thermal environment, particularly road density. Social development incorporates population density and the distribution of POI, which can indicate human activity and associated heat generation. Topography and landforms assess the effect of natural terrain features, such as elevation and distance to the coastline, on local temperatures. Fifteen characteristics were selected from these dimensions based on their relevance to the urban thermal environment, as supported by reference [18] and data availability. Each characteristic was chosen to represent a distinct aspect of the built environment that could potentially affect surface temperatures. Table 2 summarizes the calculation methods for each of these characteristics.

Fig. 3.

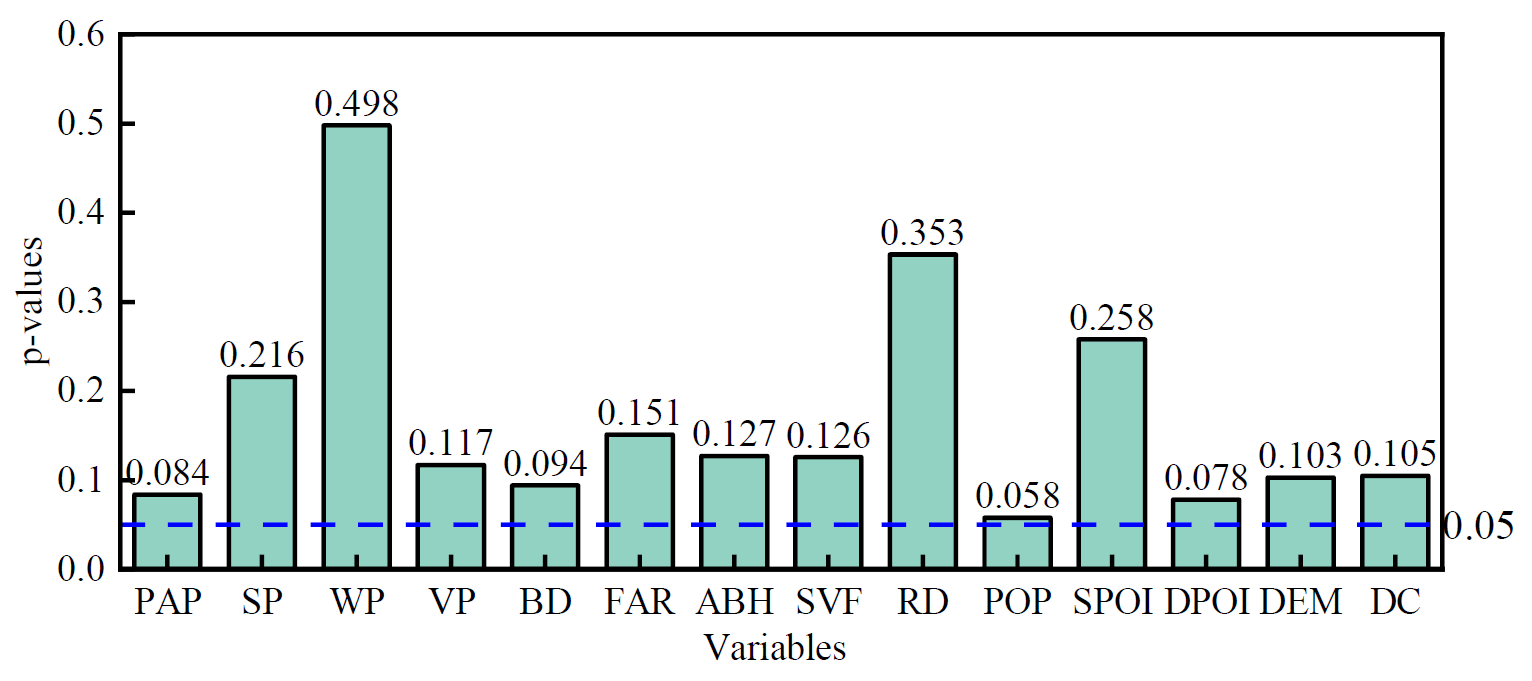

It is important to consider whether the distribution of the data follows a normal distribution, as well as to determine the assumptions and limitations in the statistical methods used when analyzing the effects of multiple independent variables on the dependent variable and select the appropriate method for data analysis. In this study, a normality test was conducted on the morphological characteristic data of the divided units, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to examine whether the data of the 15 indicators followed a normal distribution. Detailed results of the tests are shown in Fig. 4.

The p-values for all variables are less than 0.05, indicating that the data samples do not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, it is necessary to consider using non-parametric statistical methods to handle and analyze the data. It is necessary to choose a model suitable to analyze the relationship between the variables and surface temperature and that is applicable to non-normal data.

Table 2.

| Index | Abbreviation | Calculation method | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impermeable area percentage | PAP | [TeX:] $$P_{\text {Land }}=\left(\sum_1^n S_i\right) / S_U \times 100$$ | % |

| Bare soil percentage | SP | % | |

| Water percentage | WP | % | |

| Vegetation percentage | VP | % | |

| Building density | BD | Building coverage area/block total area | % |

| Floor area ratio | FAR | [TeX:] $$F A R=S_J / S_U$$ | / |

| Average building height | ABH | [TeX:] $$A B H=\left(\sum_1^n H_i\right) / n$$ | m |

| Sky view factor | SVF | - | / |

| Road density | RD | Length of road/block total area [TeX:] $$R D=\left(\sum_1^i L_i\right) / S_U$$ | / |

| Population density | POP | Population/block total area | persons/hm2 |

| Sum of factories | SF | - | pieces |

| Sum of POI | SPOI | - | pieces |

| Density of POI density | DPOI | Sum of POI/block total area | pieces/m2 |

| Digital elevation model | DEM | Elevation/block total area | m |

| Distance to coastline | DC | - | m |

3.4 FNN Model

3.4.1 Dataset processing

A FNN is used for modeling and predicting functional data. Compared to traditional perceptron or multilayer perceptron models, the FNN introduces new concepts and techniques that make network training and optimization more efficient. The hierarchical structure of the FNN consists of multiple neurons, allowing for the capture of complex relationships in functional data. Additionally, the FNN combines the flexibility of neural networks with the characteristics of functional data, enabling the analysis of nonlinear, non-normal, and time-dependent data. Therefore, the FNN is applicable to functional analysis problems in various fields. The core idea of the FNN is to define a base function on the input of each neuron and calculate the output using adjustments and biases. The Keras library, developed based on the TensorFlow framework, provides various functions for model training and learning. It allows users to build neural networks with arbitrary input layers, hidden layers, and output layers according to their needs.

Before training the model, data preprocessing is crucial. The model incorporates 15 morphology indicators of built environments, which are represented by different units and value ranges. There are significant data magnitude differences among the 15 indicators, and to enhance the model’s performance, the data must be normalized to minimize the impact of varying units of measurement. Min–Max normalization, also referred to as feature scaling, is utilized as a normalization technique. Its purpose is to ensure that each feature holds equal significance within the model and prevent any particular feature from exerting a more substantial influence due to its larger value range. The formula for Min–Max normalization is as follows:

During the model construction process, the dataset is initially randomly split into a training set (75% of the data) and a test set (25% of the data). However, to further refine the evaluation, mitigate the impact of randomness associated with a single dataset division, and make full use of all samples in the dataset, K-fold cross-validation is employed. This approach helps evaluate the model’s generalization ability across different data subsets and reduces the randomness introduced by a single dataset division. In this study, the training set is divided into five folds, with each fold serving as a validation set in turn during the five-fold cross-validation process. The model’s performance metrics are then computed on the test set, and the average performance across all five iterations is calculated.

3.4.2 Model training

In this study, the proposed FNN is built on Python and TensorFlow deep learning frameworks. The input layer includes 15 spatial morphological indicators representing the built environment characteristics of the study area. After assigning weights to the input features, the information is propagated through the hidden layers. To mitigate overfitting and underfitting, the number of hidden layers is carefully controlled. A common practice in neural network design is setting the number of hidden layer nodes to approximately 2n. The FNN model consists of one input layer, with two hidden layers and one output layer. The model employs 32 nodes in the first hidden layer and 16 nodes in the second one. The Adam optimizer is used for training, while the mean squared error (MSE) serves as the loss function (Eq. 3).

To represent the nonlinear relationship between spatial form representation indicators and the thermal environment, the “tanh” function is used as the activation function, and the mathematical expression is as follows:

The model’s learning rate is set to 0.001, the number of training epochs is set to 50, and the other parameters are left at their default settings. The model is trained until it automatically converges, indicating the completion of neural network model training.

3.5 SHAP Values

SHAP, a widely used method for interpreting machine learning models, aids in clarifying the prediction mechanisms of deep learning models. By computing SHAP values, it is possible to analyze the contribution from each factor to the forecasts of the model. This enables a deeper understanding of how each built environment factor influences the LST. The SHAP model is based on the principle of the Shapley value in cooperative game theory. It attributes a specific SHAP value per feature, which quantifies the feature’s contribution to the overall forecast of the model. It is helpful to assess the impact of individual features on the model results. The SHAP value of one feature is expressed as follows:

(5)

[TeX:] $$\phi_j(v a l)=\sum_{S=\left\{x_1, \ldots, x_p\right\} \backslash\left\{x_i\right\}} \frac{|S|!(p-|S|-1)!}{p!}\left(v a l\left(S \cup\left\{x_j\right\}\right)-v a l(S)\right)$$where the SHAP value for feature j is represented by [TeX:] $$\phi_j(v a l),$$ with S denoting the subset of features used in the model. The feature value vector of the instance being explained is represented by x, and p refers to the total number of features considered. val(S) represents the marginal contribution of a feature based on the subset S, which is given by Eq. (6):

(6)

[TeX:] $$\operatorname{val}_x(s)=\int \hat{f}\left(x_1, \cdots, x_p\right) d P_{x \neq S}-E(\hat{f}(X))$$A positive SHAP value indicates a positive contribution of the feature to the prediction result, a negative SHAP value indicates a negative contribution, and a SHAP value close to 0 indicates a small or negligible contribution.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1 Modeling Results

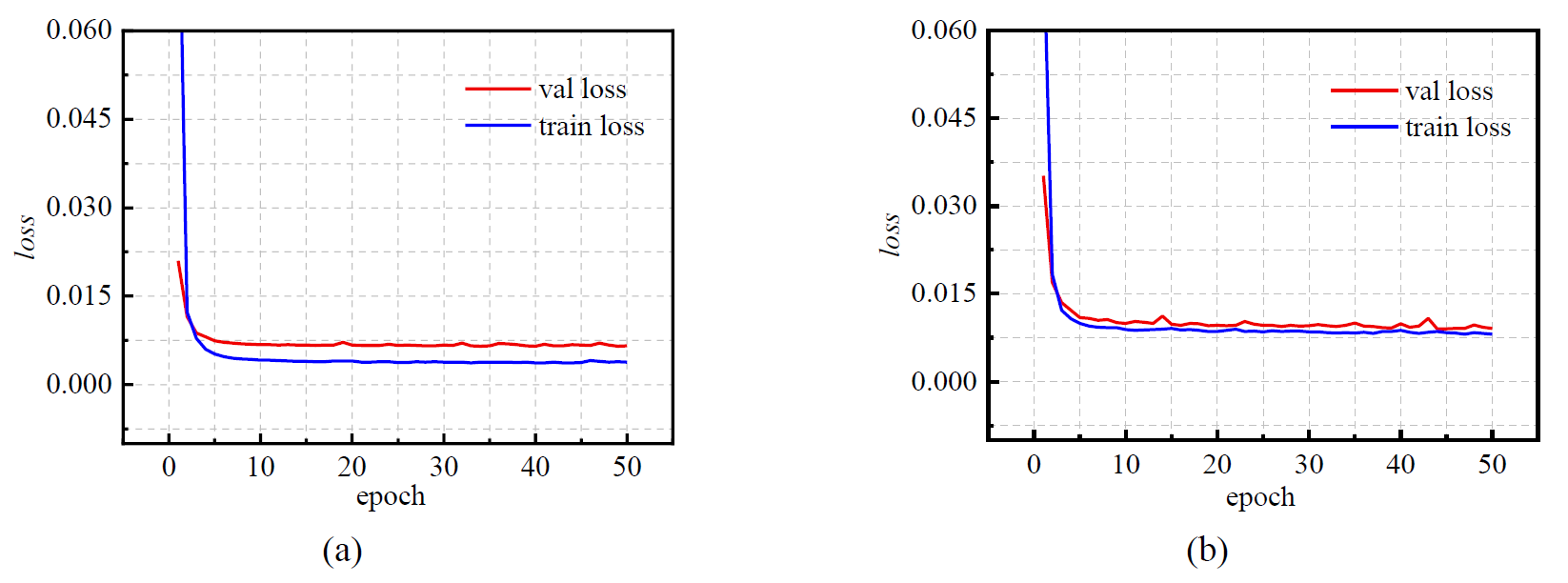

Fig. 5 shows the loss curve distribution of the two models during the training process. In the initial 50 iterations, the loss curve exhibits only minor fluctuations, remaining relatively consistent without any significant increases or sharp drops. The test set loss curve in the summer FNN model starts to fluctuate smoothly after dropping to about 0.0075, and similarly, the test set loss curve in the winter gradually smooths out after dropping to about 0.008. This suggests that the model is able to effectively fit the trained data while maintaining its generalization ability.

According to the spatial distribution maps of various indicators and the winter and summer land temperature maps in the study area, there is a certain relationship between the LST in the built-up area and land cover factors. Taking summer as an example, the higher the proportion of impermeable surfaces, the lower the vegetation coverage; the higher the building density, the denser the road network; and the higher the population density, the higher the land temperature. However, quantitatively depicting the interaction between these factors is currently not feasible.

In order to evaluate the accuracy of the proposed FNN model, we built models using the same dataset to investigate the correlation between LST and various morphological indicators through MLR and RF. In constructing the RF model, 100 weak classifiers (decision trees) were used, with the maximum tree depth set to 30. The MSE was employed as the performance metric, and the dataset was divided into 75% for training and 25% for validation. We compared the effects of MLR, RF, and FNN models in predicting the relationship between block unit morphology indicators and LST. The accuracy of these models was evaluated using the root mean squared error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) metrics. Table 3 presents the coefficient of errors for the MLR, RF, and neural network models. The results show that the FNN model outperforms both the ordinary least squares (OLS) and RF models, achieving lower RMSE and MAE values, which indicates higher accuracy in predicting the relationship between built environment factors and LST. In conclusion, the trained FNN model provides a more accurate representation of the correlation between urban spatial factors and the thermal environment, offering a more reliable basis for urban planning and environmental management.

Table 3.

| Model | Summer | Winter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| Multiple linear regression | 0.0813 | 0.0409 | 0.0991 | 0.0773 |

| Random forest | 0.0830 | 0.0420 | 0.1030 | 0.0760 |

| Feed-forward neural network | 0.0811 | 0.0406 | 0.0955 | 0.0728 |

4.2 Impact Mechanism Analysis

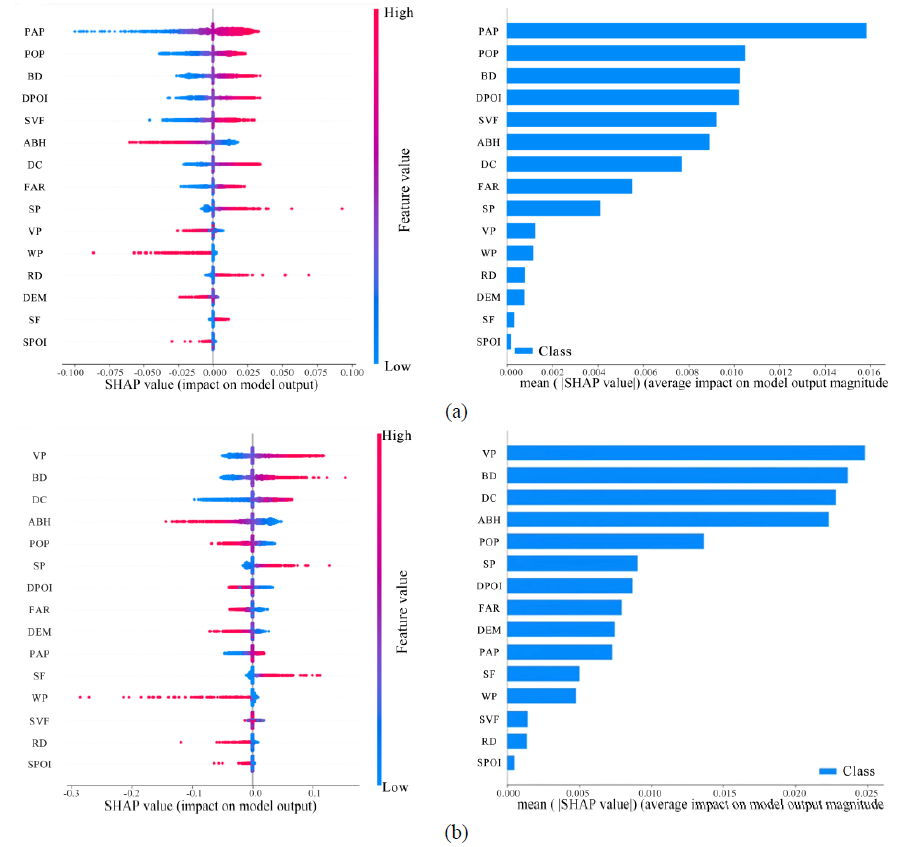

After training the FNN model, the SHAP method was applied to recognize the impact mechanisms of 15 built-up environment factors on LST. Fig. 6 shows the impact of all factors on the proposed model using a honeycomb plot, with the bar lengths corresponding to the mean contributed rate of all factors to the trained FNN. Fifteen factors are organized by their average absolute SHAP values in descending order. Each point in the plot represents a data entry from the dataset, with the SHAP value shown along the horizontal axis. The bar graphs show how much each built environment factor affects the LST in the model and are arranged in descending order.

4.2.1 Impact mechanism of the thermal environment in summer

Fig. 6 shows that within the constructed model for predicting LST in the summer built environment, of the 15 factors, 10 factors (PAP, POP, BD, DPOI, SVF, DC, FAR, SP, RD, and SF) positively influence LST prediction, while 5 factors (ABH, VP, WP, DEM, and SPOI) have a negative influence (See Table 1 for abbreviations). Notably, the impervious area percentage (PAP) [19] stands out as the most significant factor, contributing over 0.15, highlighting its strong influence on LST prediction. Moreover, POP, BD [20], and DPOI significantly contribute to LST in the summer. In contrast, SPOI has the smallest impact on LST prediction among all the evaluated factors.

When predicting LST in the summer built environment, the impervious area percentage (PAP) emerges as a crucial factor. A higher impervious surface ratio leads to greater solar radiation being transformed into heat, reducing heat storage and release, and consequently resulting in elevated LSTs. Thus, regulating the impervious surface ratio through measures such as increasing green spaces or employing permeable materials can effectively mitigate LST. Additionally, a higher population density is typically linked with increased buildings and human activities, which in turn release a significant amount of heat, contributing to higher LSTs. Furthermore, the DPOI exerts a greater influence on LST compared to the SPOI, potentially due to a higher DPOI resulting in increased building and surface coverage in the study area, leading to delayed heat accumulation and release, thereby elevating the LST. Conversely, when the total number of POI is low, the coverage of buildings and hardened surfaces in the study area is relatively reduced, resulting in accelerated heat accumulation and release, thus exerting a smaller impact on temperature.

4.2.2 Impact mechanism of the thermal environment in winter

According to Fig. 6(b), in the winter built environment surface temperature prediction model, six factors (VP, BD, DC, SP, PAP, and SF) positively impact surface temperature prediction, while nine factors (ABH, POP, DPOI, FAR, DEM, WP, SVF, RD, and SPOI) have a negative impact. Among these factors, VP has the highest contribution in the constructed model, indicating its strong influence on the predicted values across all samples. Other factors, such as BD, DC, and SP, also have significant contributions to surface temperature prediction.

During the winter, vegetation plays a crucial role in preventing heat loss and reducing temperature decrease. Therefore, increasing the vegetation coverage rate can lead to a slight increase in winter surface temperature. On the other hand, a higher building density can lead to higher absorption of solar radiation [21] and heat generation, resulting in elevated surface temperatures. The DC may affect the regulation of surface temperature by sea breezes, while an increase in SP can lead to more energy being absorbed by the surface, consequently raising the surface temperature. Furthermore, the ABH has a negative impact on the winter surface temperature, which aligns with previous research findings.

This study successfully reveals the nonlinear correlation between urban built environment features and the thermal environment with FNN modeling. The SHAP method was employed to illustrate how physical features of the built-up area affect the heat environment. The proposed method is used to quantitatively analyze the impacts of different urban built-up area factors on LST. It reveals the complex mechanisms underlying the urban heat island effect. Furthermore, it offers a clear explanation for understanding the nonlinear relationship between urban built-up environment factors and the urban thermal environment. To further elucidate the impacts of these characteristics, the SHAP model is incorporated, offering insights into how individual urban built environment factors shape the thermal environment. Through proper urban planning, the living environment of urban residents can be significantly improved, providing a scientific rationale for the formulation of more effective public health policies.

4.3 Discussion

In the context of analyzing the impact of built environment characteristics on the thermal environment, FNNs offer several advantages. Firstly, they can handle large amounts of data, which is crucial given the complexity and dimensionality of the problem. Secondly, FNNs are capable of capturing intricate interactions between input variables that might be difficult to model using traditional analytical methods. This is particularly important in our case, where the relationship between built environment features and thermal comfort is likely to be nonlinear and influenced by multiple factors. While other neural network architectures, such as recurrent neural networks or convolutional neural networks, could potentially solve this problem, we chose FNNs for their simplicity, ease of implementation, and proven effectiveness in similar domains. This study represents a novel application of machine learning and model interpretation methods to analyze the impact of built environment characteristics on the thermal environment. Traditional linear analysis models have limited ability to handle complex relationships, making it difficult to comprehensively assess the variability and complexity of the thermal environment. Many scholars have used methods such as XGBoost [22], RF [23], and artificial neural network [24] to analyze data related to thermal environment studies. These methods, compared to traditional analytical models, can better handle complex relationships and nonlinear contributions and can improve the accuracy of prediction and analysis through feature selection and model optimization.

This method integrates model interpretation techniques, which provide insights into how the model makes its predictions and can inform the design of more energy-efficient and comfortable buildings. Through quantitative analysis using the SHAP model, we discovered that different factors not only vary in their importance to the thermal environment but also exhibit specific directions and threshold phenomena. This might suggest underlying complex physical mechanisms and urban planning principles. Through comparison with previous studies, we found that impervious surfaces and vegetation are important factors affecting the thermal environment, which is similar to the results of Wang's study [25]. The results of this study, conducted in coastal areas, show that natural factors play a dominant role in the summer thermal environment. However, in the study of the Yangtze River Delta heat island, the impact of human factors in the cities of Nantong and Jiaxing on the thermal environment exceeds that of natural factors. This may be due to differences in the economic development level and geographical locations of the regions. Additionally, this study found that the average building height has a negative impact on summer LST in the study area and is a major factor in reducing summer surface temperature. This is similar to empirical results in Beijing [26], which show that taller buildings have better shading ability, reducing the duration of direct sunlight on the surface. In contrast, the influence of vegetation coverage on LST is relatively small. It is worth noting that in most previous studies, vegetation coverage was considered one of the most important factors affecting summer temperatures [20]. Furthermore, building height has a negative impact on winter LST. This is different from previous studies showing a positive correlation between high-rise buildings and winter LST. There may be certain regional differences, which could be due to differences in the spatial configurations of different cities and underlying climatic conditions. This interpretability aspect is crucial for gaining trust in the model's predictions and ensuring that the results are actionable for practitioners.

Our method demonstrates remarkable efficiency, enabling the processing of large-scale datasets within a short timeframe. This advantage is complemented by its high predictive accuracy, outperforming traditional methods in several benchmarks. Moreover, while our method has shown promising performance across various datasets, its generalization ability remains to be thoroughly evaluated and enhanced. Furthermore, we will continue exploring ways to enhance the model’s generalization capability, ensuring its applicability in a broader range of contexts. Comparing the findings of this study with previous research, future studies should consider various factors, including geography, climate, and economy, in a comprehensive manner. From a macro perspective, it is essential to consider elements such as buildings, green spaces, water bodies, climate, and economy in order to provide targeted recommendations and decision support for urban planning. Furthermore, future research can explore the implementation of sustainable technologies to regulate the thermal environment, such as the utilization of green roofs and geothermal energy. By introducing innovative technologies and solutions, it is possible to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change on the thermal environment, thereby enhancing the adaptive capacity and sustainability of cities.

5. Conclusion

Recent studies on urban thermal environments have focused on the overall city, overlooking more detailed analyses of built-up areas. In contrast, this study specifically targeted built-up coastal regions to examine how the characteristics of the built environment influence the thermal environment. Utilizing multi-source data, we identified 15 key built environment factors affecting a city’s physical thermal environment across multi-dimensions. We trained a high-precision FNN to accurately capture the complex nonlinear correlations between built-up area factors and LSTs.

The results show that the FNN outperformed the MLR and RF models, as evidenced by its lower RMSE and MAE. This indicates that the trained FNN is more effective at capturing the nonlinear relationship between the built-up environment and the thermal environment. The SHAP method was utilized to interpret the black-box nature of the nonlinear machine learning model, providing a quantitative explanation of how 15 factors influence LST. An analysis of the LST forecast model for built environments in both the summer and winter revealed that building density is a key factor, exhibiting a high contribution value and playing a vital role in modeling the thermal environment of coastal cities. Furthermore, seasonal variations in the interpreted results indicate that factors such as an impervious surface percentage, proximity to the coastline, vegetation cover, and sky openness contribute differently to surface temperature predictions depending on the season. This suggests that the impact of built environment characteristics on coastal surface temperatures varies significantly throughout the year.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the extended version of “Explore the Impact mechanism of urban built environment on thermal environment based on deep machine learning,” in the 15th International Conference on Computer Science and its Applications (CSA 2023) held in Nha Trang, Vietnam, dated December 18-20, 2023.

Biography

Yansu Qi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4316-696XShe received a Ph.D. from the School of Environmental and Municipal Engineering from Qingdao University of Technology in 2024. She is currently a lecturer at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at Qingdao University of Technology. Her current research interests include landscape eco-planning for wetlands.

Biography

Biography

Biography

References

- 1 S. Yuan, Z. Ren, X. Shan, Q. Deng, and Z. Zhou, "Seasonal different effects of land cover on urban heat island in Wuhan's metropolitan area," Urban Climate, vol. 49, article no. 101547, 2023. https://doi.org/10.10 16/j.uclim.2023.101547doi:[[[10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101547]]]

- 2 G. Mussetti, E. L. Davin, J. Schwaab, J. A. Acero, J. Ivanchev, V . K. Singh, L. Jin, and S. I. Seneviratne, "Do electric vehicles mitigate urban heat? The case of a tropical city," Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol. 10, article no. 810342, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.810342doi:[[[10.3389/fenvs.2022.810342]]]

- 3 H. R. Heshmat Mohajer, L. Ding, D. Kolokotsa, and M. Santamouris, "On the thermal environmental quality of typical urban settlement configurations," Buildings, vol. 13, no. 1, article no. 76, 2023. https://doi.org/10. 3390/buildings13010076doi:[[[10.3390/buildings13010076]]]

- 4 P. Pacheco and E. Mera, "Evolution over time of urban thermal conditions of a city immersed in a basin geography and mitigation," Atmosphere, vol. 14, no. 5, article no. 777, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos 14050777doi:[[[10.3390/atmos14050777]]]

- 5 Z. Dongmiao, L. Yufeng, Z. Guangzhao, W. Xingtian, M. Sheng, and G. Weijun, "A knowledge-based human-computer interaction system for the building design evaluation using artificial neural network," Human-Centric Computing and Information Sciences, vol. 13, article no. 2, 2023. https://doi.org/10.22967/ HCIS.2023.13.002doi:[[[10.22967/HCIS.2023.13.002]]]

- 6 S. L. Handy, M. G. Boarnet, R. Ewing, and R. E. Killingsworth, "How the built environment affects physical activity: views from urban planning," American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 64-73, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00475-0doi:[[[10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00475-0]]]

- 7 G. Guerri, A. Crisci, A. Messeri, L. Congedo, M. Munafo, and M. Morabito, "Thermal summer diurnal hotspot analysis: the role of local urban features layers," Remote Sensing, vol. 13, no. 3, article no. 538, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13030538doi:[[[10.3390/rs13030538]]]

- 8 Y . C. Chiang, H. H. Liu, D. Li, and L. C. Ho, "Quantification through deep learning of sky view factor and greenery on urban streets during hot and cool seasons," Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 232, article no. 104679, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104679doi:[[[10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104679]]]

- 9 G. Y . Oukawa, P. Krecl, and A. C. Targino, "Fine-scale modeling of the urban heat island: a comparison of multiple linear regression and random forest approaches," Science of the Total Environment, vol. 815, article no. 152836, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152836doi:[[[10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152836]]]

- 10 Y . Gao, J. Zhao, and L. Han, "Quantifying the nonlinear relationship between block morphology and the surrounding thermal environment using random forest method," Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 91, article no. 104443, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104443doi:[[[10.1016/j.scs.2023.104443]]]

- 11 M. M. Bukhari, S. S. Ullah, M. Uddin, S. Hussain, M. Abdelhaq, and R. Alsaqour, "An intelligent model for predicting the students' performance with backpropagation neural network algorithm using regularization approach," Human-Centric Computing and Information Sciences, vol. 12, article no. 44, 2021. https://doi.org/ 10.22967/HCIS.2022.12.044doi:[[[10.22967/HCIS.2022.12.044]]]

- 12 Z. Dai, T. Li, Z. R. Xiang, W. Zhang, and J. Zhang, "Aerodynamic multi-objective optimization on train nose shape using feedforward neural network and sample expansion strategy," Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics, vol. 17, no. 1, article no. 2226187, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/19942060. 2023.2226187doi:[[[10.1080/19942060.2023.2226187]]]

- 13 J. de-Miguel-Rodriguez, A. Morales-Esteban, M. V . Requena-Garcia-Cruz, B. Zapico-Blanco, M. L. Segovia-Verjel, E. Romero-Sanchez, and J. M. Carvalho-Estevao, "Fast seismic assessment of built urban areas with the accuracy of mechanical methods using a feedforward neural network," Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 9, article no. 5274, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095274doi:[[[10.3390/su14095274]]]

- 14 J. K. Kim, K. Lee, and S. G. Hong, "Cognitive load recognition based on T-Test and SHAP from wristband sensors," Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences, vol. 13, article no. 27, 2023. https://doi.org/ 10.22967/HCIS.2023.13.027doi:[[[10.22967/HCIS.2023.13.027]]]

- 15 S. B. Jabeur, S. Mefteh-Wali, and J. L. Viviani, "Forecasting gold price with the XGBoost algorithm and SHAP interaction values," Annals of Operations Research, vol. 334, no. 1, pp. 679-699, 2024. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10479-021-04187-wdoi:[[[10.1007/s10479-021-04187-w]]]

- 16 J. Park, W. H. Lee, K. T. Kim, C. Y . Park, S. Lee, and T. Y . Heo, "Interpretation of ensemble learning to predict water quality using explainable artificial intelligence," Science of the Total Environment, vol. 832, article no. 155070, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155070doi:[[[10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155070]]]

- 17 H. Nishikawa, J. Oenema, F. Sijbrandij, K. Jindo, G. J. Noij, F. Hollewand, et al., "Dry matter yield and nitrogen content estimation in grassland using hyperspectral sensor," Remote Sensing, vol. 15, no. 2, article no. 419, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15020419doi:[[[10.3390/rs1509]]]

- 18 Y . Gao, J. Zhao, and K. Yu, "Effects of block morphology on the surface thermal environment and the corresponding planning strategy using the geographically weighted regression model," Building and Environment, vol. 216, article no. 109037, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109037doi:[[[10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109037]]]

- 19 S. Ghosh, D. Kumar, and R. Kumari, "Assessing spatiotemporal variations in land surface temperature and SUHI intensity with a cloud based computational system over five major cities of India," Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 85, article no. 104060, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.104060doi:[[[10.1016/j.scs.2022.104060]]]

- 20 Z. Wu, Z. Tong, M. Wang, and Q. Long, "Assessing the impact of urban morphological parameters on land surface temperature in the heat aggregation areas with spatial heterogeneity: a case study of Nanjing," Building and Environment, vol. 235, article no. 110232, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110232doi:[[[10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110232]]]

- 21 X. Yao, Z. Zhu, X. Zhou, Y . Shen, X. Shen, and Z. Xu, "Investigating the effects of urban morphological factors on seasonal land surface temperature in a "Furnace city" from a block perspective," Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 86, article no. 104165, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.104165doi:[[[10.1016/j.scs.2022.104165]]]

- 22 D. McCarty, J. Lee, and H. W. Kim, "Machine learning simulation of land cover impact on surface urban heat island surrounding park areas," Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 22, article no. 12678, 2021. https://doi.org/10. 3390/su132212678doi:[[[10.3390/su13278]]]

- 23 J. Lin, S. Qiu, X. Tan, and Y . Zhuang, "Measuring the relationship between morphological spatial pattern of green space and urban heat island using machine learning methods," Building and Environment, vol. 228, article no. 109910, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109910doi:[[[10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109910]]]

- 24 V . Equere, P. A. Mirzaei, S. Riffat, and Y . Wang, "Integration of topological aspect of city terrains to predict the spatial distribution of urban heat island using GIS and ANN," Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 69, article no. 102825, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102825doi:[[[10.1016/j.scs.2021.102825]]]

- 25 Z. Wang, Q. Meng, M. Allam, D. Hu, L. Zhang, and M. Menenti, "Environmental and anthropogenic drivers of surface urban heat island intensity: a case-study in the Yangtze River Delta, China," Ecological Indicators, vol. 128, article no. 107845, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107845doi:[[[10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107845]]]

- 26 B. Liu, X. Guo, and J. Jiang, "How urban morphology relates to the urban heat island effect: a multi-indicator study," Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 14, article no. 10787, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410787doi:[[[10.3390/su151410787]]]